Gaelic in Southwest Scotland

Gaelic was once widely spoken across Scotland, including the southwest region. It was the language of the common people, and it deeply influenced the region’s cultural practices, folklore, and traditions. However, the use of Gaelic began to decline with the increasing influence of Scots and English, particularly after the 17th century.

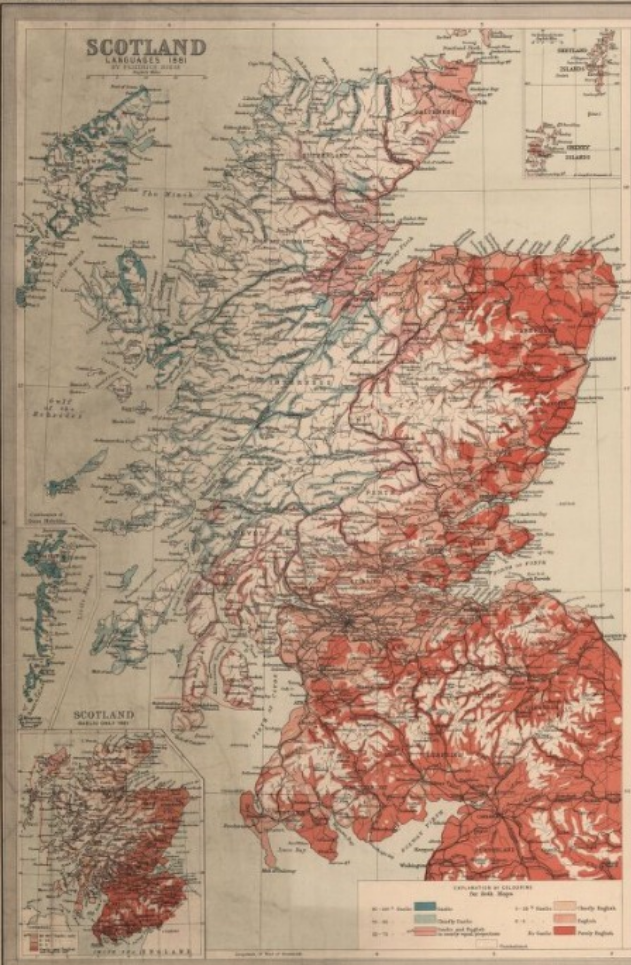

Map of Ayr around 1901, indicating a prevalence of up to 5% of Gaelic speakers.

Southwest Scotland Clearances

The clearances in Southwest Scotland, similar to the Highland Clearances, involved the forced eviction of tenants to make way for large-scale sheep farming and other agricultural changes. This process had a profound impact on Gaelic culture and language. Many of those evicted were Gaelic speakers, and the disruption of their communities led to a further decline in the use of the language.

The long Covenanting tradition of south-west Scotland was important. The restoration of King Charles II in 1660 led once again to the rule of bishops in the Presbyterian church. This action was thought heretical and oppressive by many pious communities and their ministers, and in open conflict with the sacred Covenants between Christ and his church established during the civil wars of the 1640s. As a result, many clergymen left their parishes and held alternative open-air services or conventicles. These were soon outlawed by the state as treason and the army then enforced the will of the King, often in a particularly brutal fashion.

From The Scottish Clearances: A History of the Dispossessed, 1600-1900 by Tom Devine

The clearances not only displaced people but also disrupted the transmission of cultural knowledge and traditions, which were often passed down through the Gaelic language. This period marked a significant shift in the cultural landscape of Southwest Scotland, as English and Scots became more dominant.

Education (Scotland) Act 1872

The Education (Scotland) Act 1872 played a crucial role in promoting the speaking of English over Gaelic. The act established a system of compulsory education, but it also enforced English as the primary language of instruction.

This policy further marginalized Gaelic, as children were often discouraged or even punished for speaking their native language in school. The act accelerated the decline of Gaelic, as successive generations were educated primarily in English.

By the 19th century Gaelic was very much a minority language in the county of Ayr – according to the Census only 1700 Gaelic speakers were left in 1901.

Burns and Gaelic culture

The attrition of Gaelic culture is one of the reasons that Robert Burns has such an important part in the cultural history of Scotland. Around 30 of his 600 song lyrics are based on Gaelic tunes – these tunes would in all probability have disappeared from Scotland’s culture were it not for their being used as the melody for Burns’ songs.

Cultural Legacy

Today, Gaelic’s influence in Southwest Scotland is subtle, preserved in place names, folklore, and some cultural practices. Many of the songs Burns collected were of Gaelic orgin, passed from one generation to the next.

Whatever view you take, Ayrshire and Dunure had a significant Gaelic heritage, suppressed in many ways over the centuries but persisting in folk memory.

Efforts to revive and preserve Gaelic have gained momentum in recent years, with initiatives aimed at promoting the language and its cultural heritage.